So…after being away from racing while employed at DHS (a rather “not what I thought is was going to be” type of experience,) I decided to look for employ where I could (actually) use my technical skills from my post-grad degree. After all, why endure all that effort, expense, and time only to not use it? This decision led me to new job-field entry discussions with WSDOT, which led to a certification in an ESRI GIS course, certification in the Python 3 programming language, and a professional certification in IBM data science. Moving right along, I’m happily absorbing specialty courses in machine learning (really fun stuff by the way.)

By the nature of my blog, you know that I like to use tools at hand to examine, evaluate, and improve the processes I’m interested in, namely, improving my physiological systems in order to accomplish my racing goals. One of the tools I’ve used in the past was the BSX Insight device. In early 2018, BSX Technologies decided to discontinue support for the monitor effectively turning it into a brick; much to my disappointment. (And that’s saying it nicely.) That was about $300 USD out of my wallet so the news was not received lightly. My 2nd generation monitor started gathering dust.

Then I found this: Start BSX without the app or internet using an Android device. Basically, the author used the nRF Connect App in an Android device to connect and start the BSX Insight monitor. What? I had already used this App to diagnose other BLE hardware but did not know the specific write values and specific UUIDs to start my monitor.

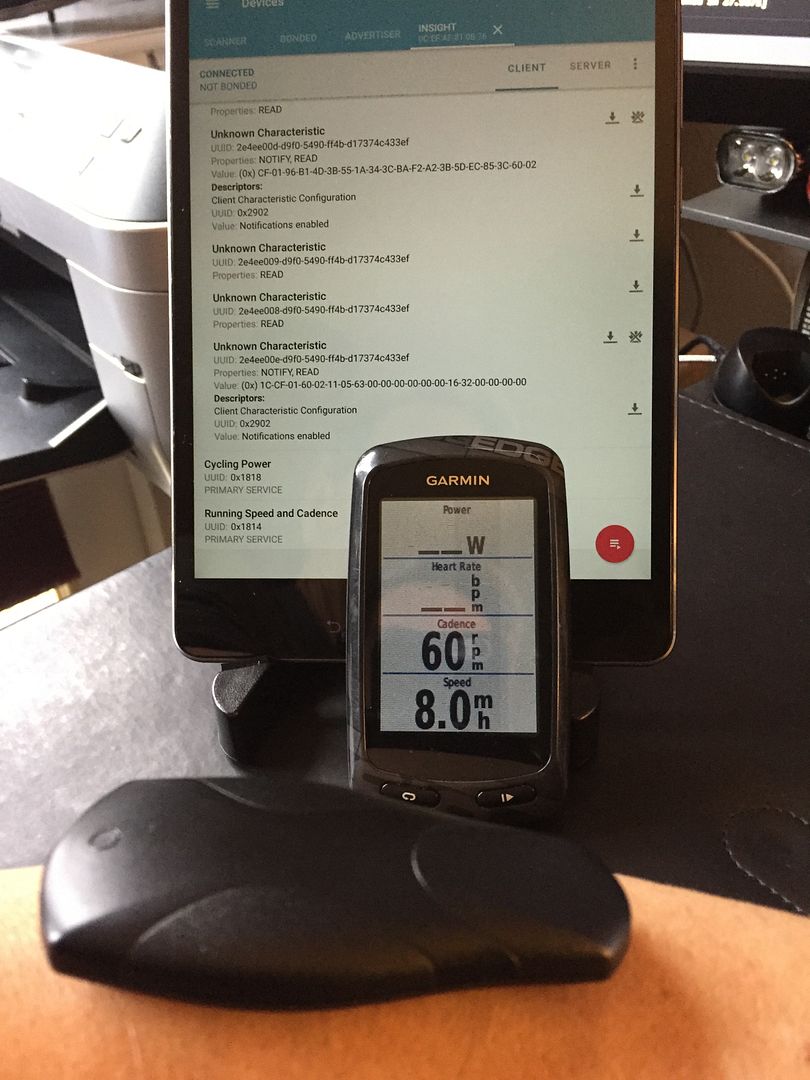

I had to try this windfall. Incredulously, while my tablet was starting, I dug out my Garmin Edge 810 head unit, powered-up, and selected the BSX sensor feed profile I set up so long ago. I scrambled back to the tablet. Opened the nRF Connect App, enabled the (3) notification characteristics, and then wrote the hexadecimal value “0402” to the UUID indicated in the blog post above annnnddd…

DATA STREAM!

I couldn’t believe it. There, on my Garmin display, were my SmO2 and tHb values happily reporting what my forearm muscle was doing energy-wise.

In Figure 1, we see the Insight monitor sitting on my forearm. Behind, my tablet shows the nRF Connect App. Between, my 810 displays the SmO2 as “rpm”, and tHb “mph” values. Note that years ago, this sensor profile using the “rpm” and “mph” labels was the only one I could utilize with the 810 model. Today, there are various other cycling devices which display the metrics correctly.

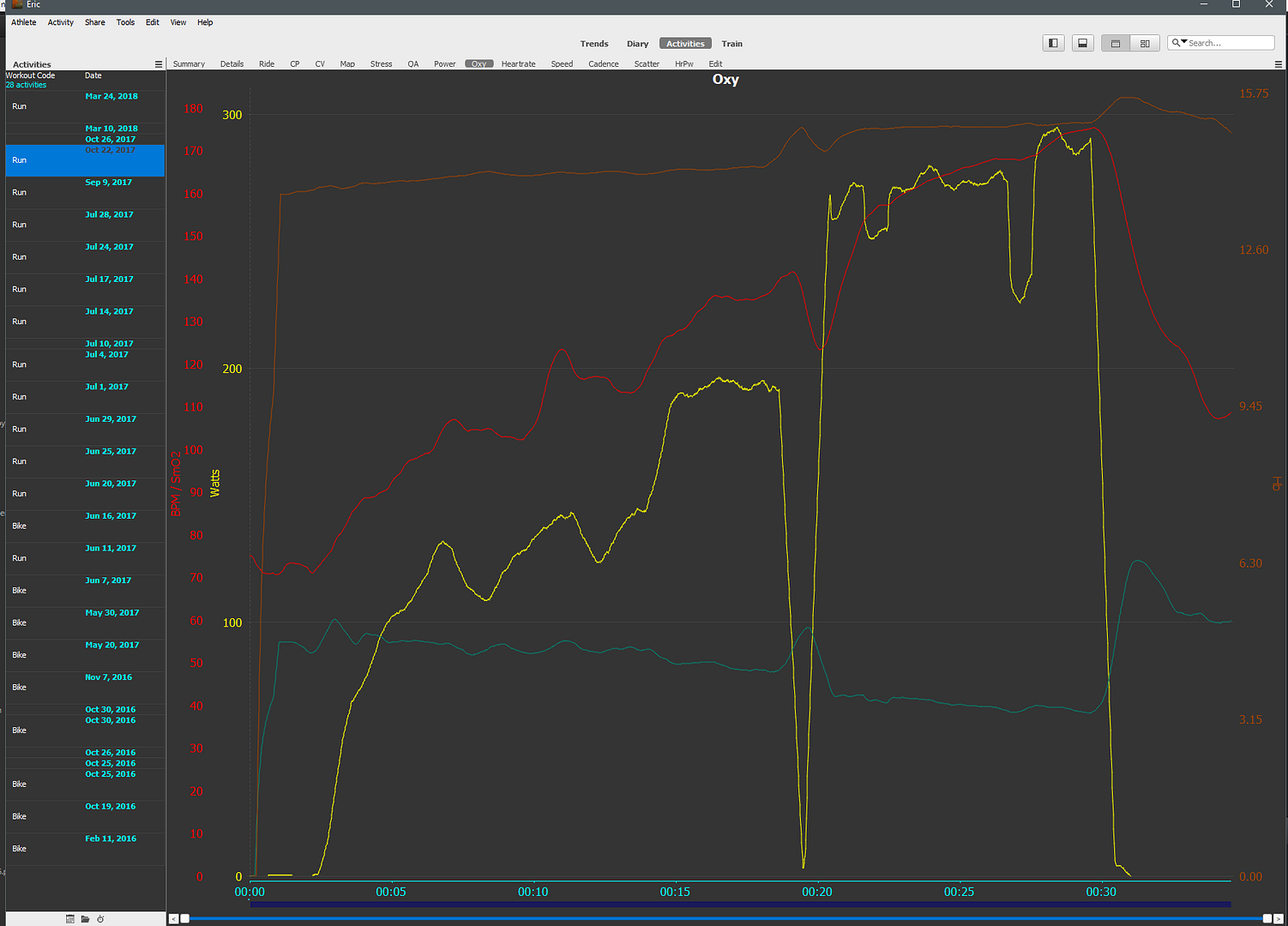

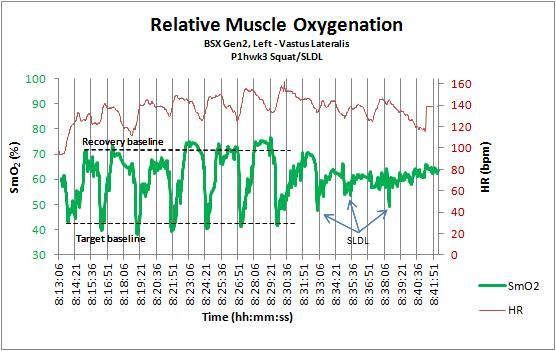

Back then, I used the very flexible and open source Golden Cheetah software (GC) to assemble all my data streams onto one display:

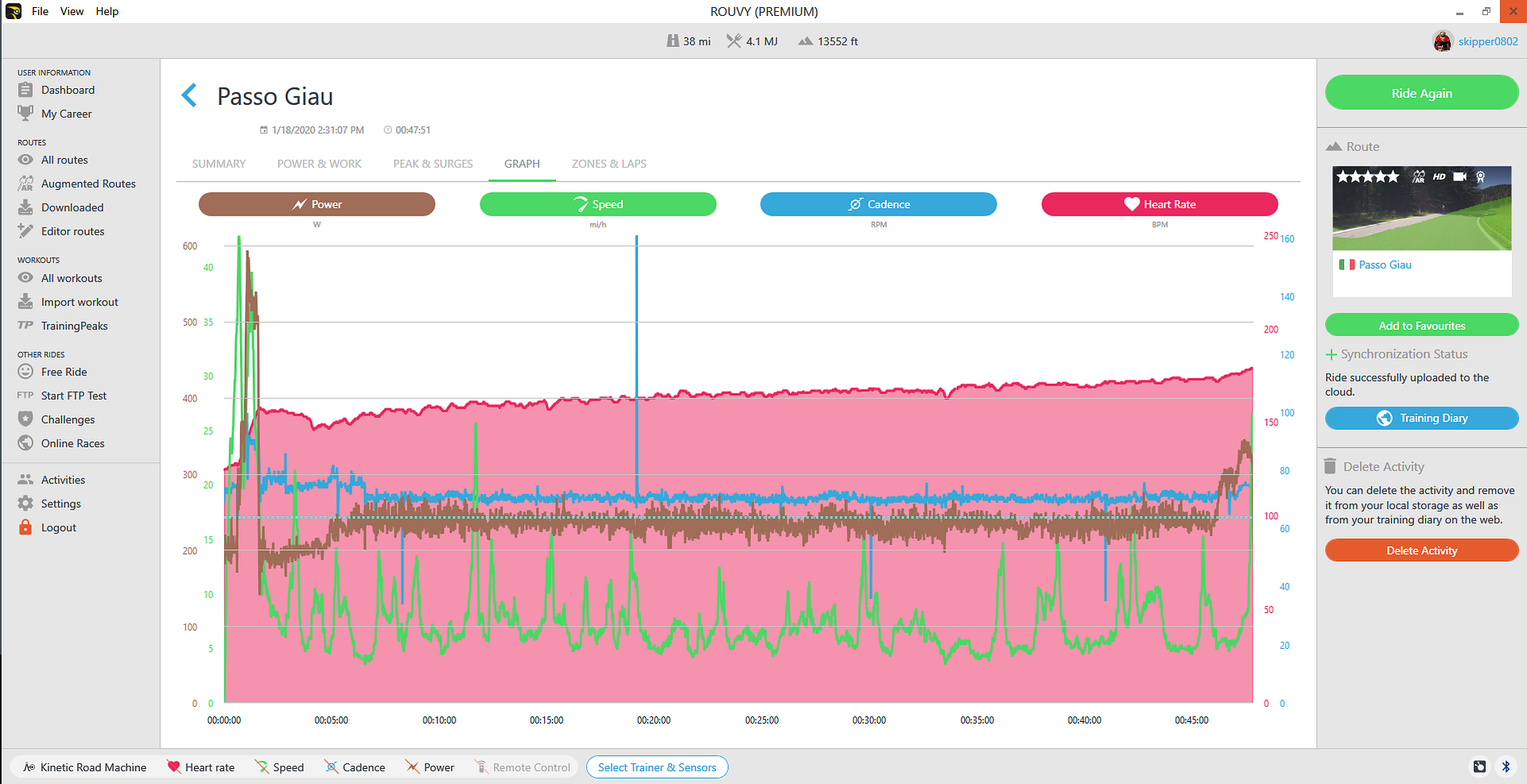

I’m sure I’ll figure out if I want to continue using GC or if another platform would be more suitable, such as Rouvy. I’m not certain that I’ll be able to configure the BSX data streams because the Rouvy App interprets the device as an rpm/speed sensor:

Figure 3 shows how Rouvy displays your post-ride measures. This example show my usual sensor input setup for a trainer session. There is a “workout” mode that I have used for HIT intervals or specific training targets, but as of this writing I’ve not verified how I might integrate the BSX streams.

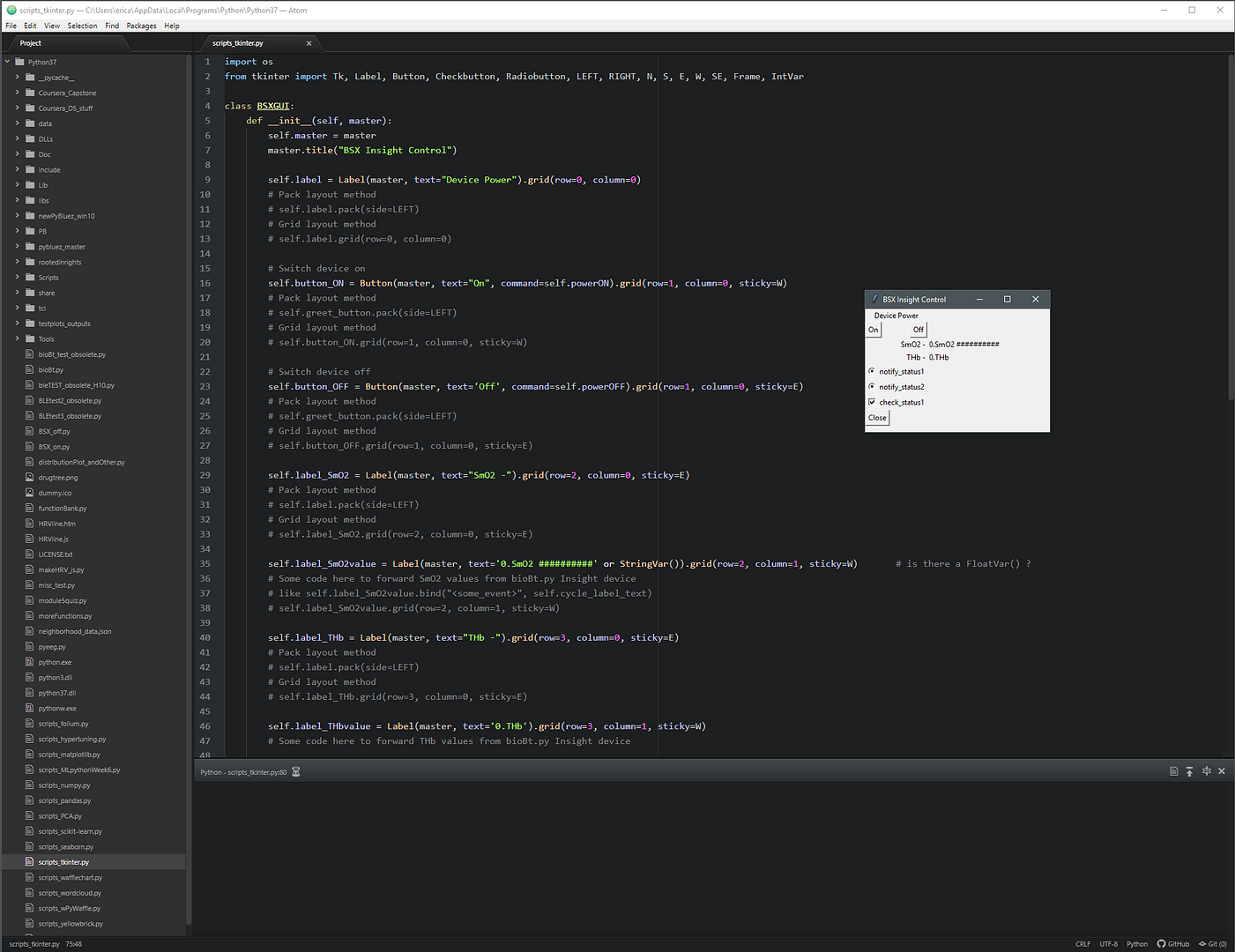

Bring on the Python skillz…

At any rate, I’ve set about building my own BSX Insight GUI/interface using Python. The first Python-Windows compatible package I’ve found is tkinter. Thus far my experience using this library to build the GUI has been lukewarm, but I just want something functional for now…I can always make it pretty later. I’m relieved that my Insight monitor will not join the group of today’s electronic detritus. It can still provide useful information.

I’ve the idea to assemble ALL of my data into one structure so that I might throw my data science skills at it in order to help answer the many questions I have about achieving physiological training goals. And that’s definitely a post in the future. I hope all of you will find what you’re looking for in this new year. Thanks for reading.

Recent Comments: